Privacy Preserving Password Cracking - The 3PC Protocol

Author: UiO

Introducing 3PC: A New Era of Privacy in Password Cracking

In today's digital age, the security of our passwords is paramount. Despite the push towards a passwordless future by giants like Apple, Google, and Microsoft, passwords remain deeply entrenched in our digital lives, especially in areas where passwordless technologies like biometrics or FIDO are impractical. Passwords are still the number one authentication mechanism, either as the primary modality, or it is part of the account recovery [1]. With this reality, the importance of up-to-date security and password management practices cannot be overstated.

However, a significant challenge arises when organizations attempt to assess the security of stored passwords—specifically, the risk involved in cracking password hashes using third-party computational resources. Traditionally, engaging an untrusted third party or cloud service to crack a password hash poses severe privacy and security risks, including the potential exposure of sensitive hash digests and the cleartext passwords derived from them.

Enter the Privacy-Preserving Password Cracking (3PC) protocol, a groundbreaking solution designed to address this dilemma. The 3PC protocol enables the utilization of third-party resources for password cracking without revealing the hash digest or the resulting cleartext password.

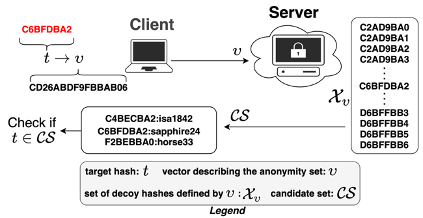

At the heart of the 3PC protocol is a simple yet powerful idea: mask the target hash within a large set of decoy hashes. This approach ensures that when the third-party server attempts to crack the hashes, it cannot distinguish the target hash from the decoys. The protocol cleverly avoids directly sending the hash to be cracked, instead sending a definition of the set that includes it. This set acts as a 'digital haystack,' effectively hiding the 'needle'—the target hash.

How Does 3PC Work:

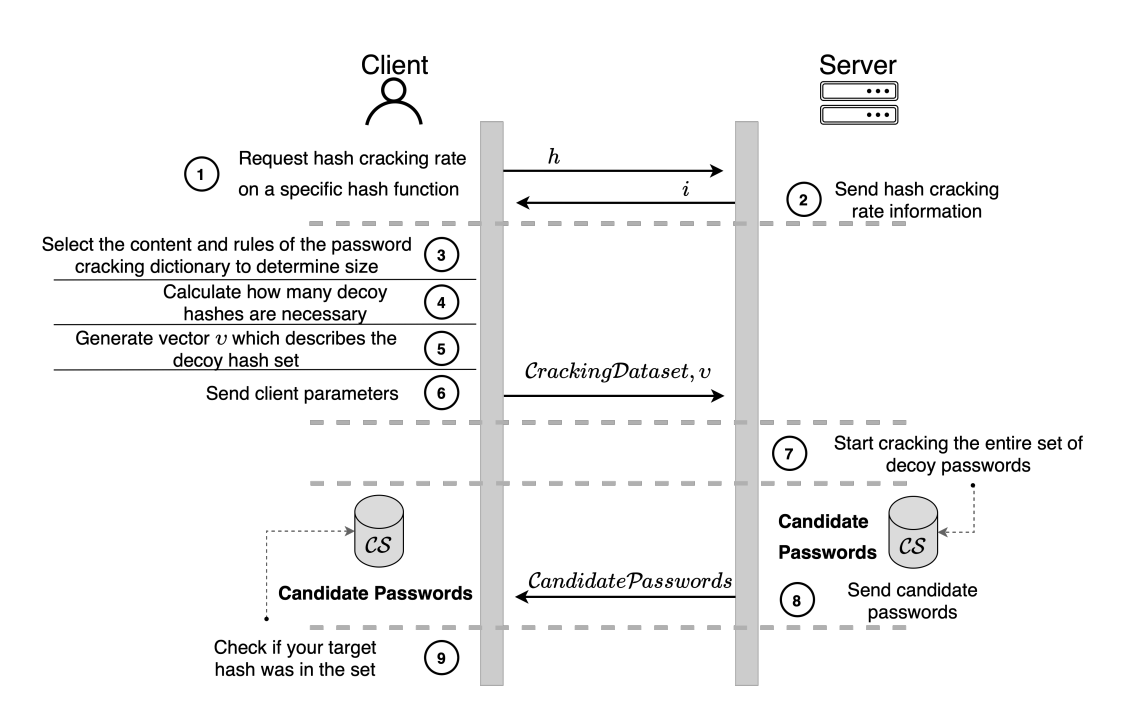

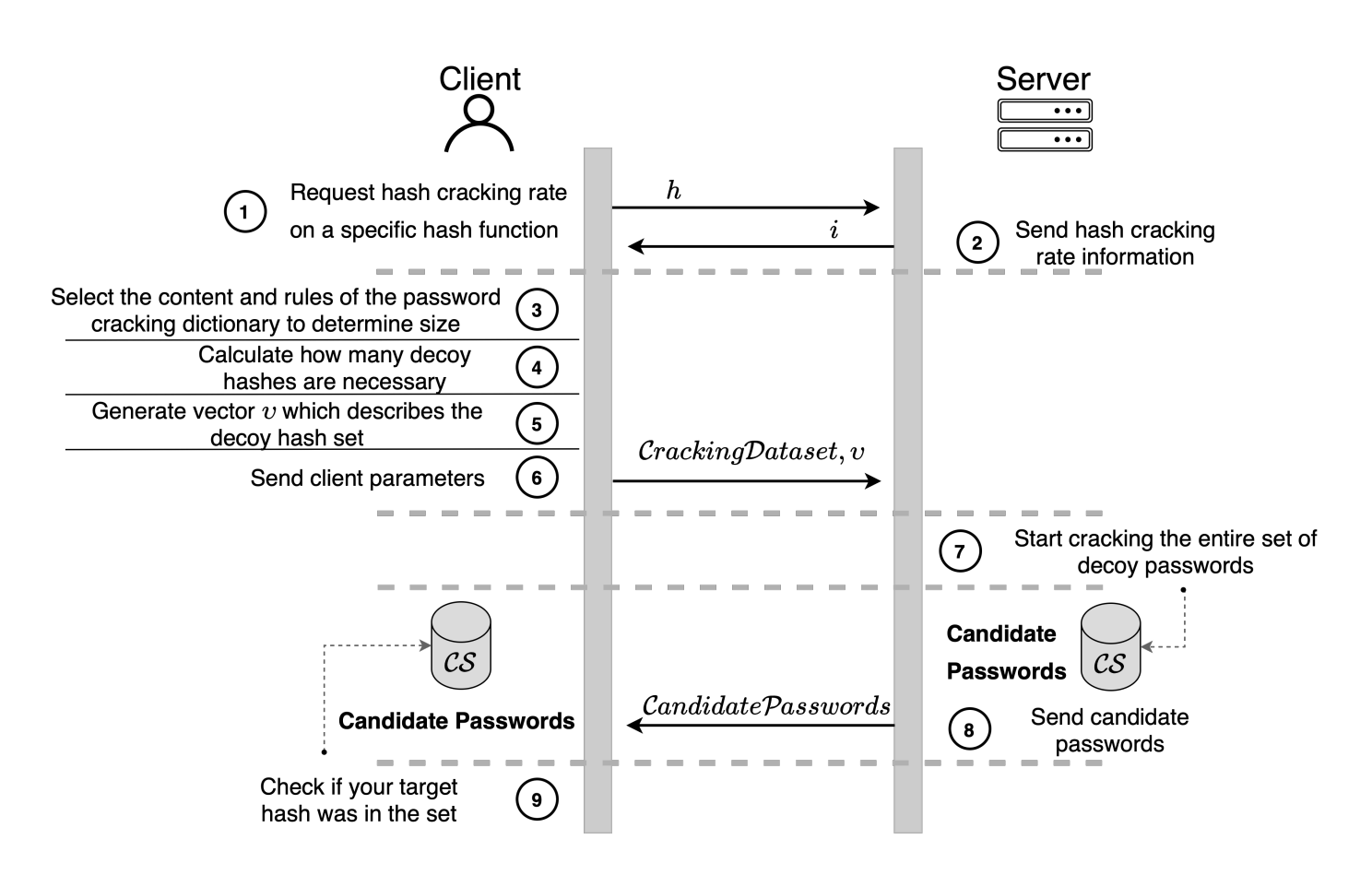

Figure 1: Sequence Diagram of the new 3PC protocol.

Step 1: Request hash rate

First the client requests the has rate information for a specific hash function. This is important to determine what is a reasonable cracking dictionary, as the server will need to hash every password requested, and then check if the resulting hash value can be found in the decoy set.

Step 2: Server Reply

The server sends back what is the hash rate for the specified hash function.

Step 3: Determine Cracking Dataset Parameters

As earlier stated the client must decide what should be the the size of the cracking dataset. Only once this size is defined, the client can proceed on selecting the content. This can be a something as simple as a database like RockYou, a brute force attack, or using a base dictionary with mangling rules.

Step 4: Generating the Decoy Set Size

The first operational step in implementing the 3PC protocol involves calculating two parameters:

- The necessary size for the set of decoy hashes that includes the target hash.

- The client side must decide how many candidate passwords it would like to get. We denote this number by “R” This set will serve as an anonymity set in case the target hash is cracked.

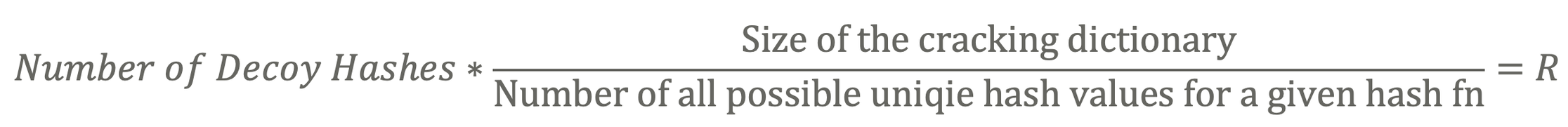

Even if it is not cracked the server will always get R candidate passwords. This will stay true based on the size of the cracking dataset, even if the content will completely change. This formula is depicted in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Formula for calculating the relation of R and the number of decoy hashes.

Step 5: Generating the Decoy Set

Next, the 3PC protocol involves generates a vector that defines the decoy hashes that includes the target hash. Importantly, the actual contents of this set are never explicitly listed or sent; only the definition is communicated, ensuring that the specifics of the target hash remain obscured. This is important, as if one would attempt to write every decoy hash value on the hard disk, it would result in Petabyetes of data, as the decoy set can easily hold 10^70 hash values. Figure 3. shows this concept with a toy example where the hash values are short. On the server side all the decoy hashes are shown for demonstration, but they will never be extracted in this way.

Figure 3: Simplified protocol.

Step 6: Cracking with Anonymity

The client simply sends the vector describing the decoy set, and the cracking dataset (this includes potential mangling rules etc.) as shown in Figure 2. The server ca now start the cracking process.

Step 7: Cracking with Anonymity

Upon receiving the definition of the decoy set, the third-party server begins the process of attempting to crack hashes in this set. In practice this means that is starts to hash values from our Cracking Dataset. The server employs its computational resources to this end, but crucially, it remains ignorant of which hash is the target. This ignorance is a deliberate feature of the protocol, ensuring that the server cannot gain any useful information about the target hash or its corresponding plaintext password. At no point will the server gain awareness whether the cracking process is successful. It must finish hashing every passwords to get approximately R candidates.

Step 8: Returning the Results

After the cracking process concludes, the server returns a list of successfully cracked hashes—along with their corresponding plaintext passwords—to the client. This list constitutes the candidate password set.

Step 9: Checking the results

The client then checks this set to determine whether the target hash has been cracked. Notably, the server is unable to ascertain whether the target hash is among those cracked, maintaining the confidentiality of the password.

Proof of Work

To assure the client that the third-party server has indeed expended the computational effort required to exhaust the agreed-upon search space, the protocol incorporates a proof of work mechanism. This step verifies that the server has performed the necessary work, lending credibility to the results of the cracking process. This simply means that the server can only get approximately R candidate passwords if it finishes the cracking process.

Where is the Catch

Is this not the same as transmitting a segment of the hash to a third party, which then proceeds to decrypt hashes that incorporate this segment, returning a collection of results, among which lies the genuine plaintext. Is this just "Have I Been Pawned" with sending a lot more resources? The answer is not exactly.

The nature of the resources is the most important: Compared to cracking a single password hash, the method established doesn't require more GPU or FPGA resources when you aim to recover 10^70 decoy hashes or just a single one. The expensive part of the cracking process doesn't change by increasing privacy requirements, which is one of the main achievements. The only real overhead is to transmit the candidate passwords, which for strict privacy requirements can be several gigabytes. Thus, the only bottleneck is network bandwidth and hdd space. The latter is very important, as brute force attacks can be rendered infeasible because they would produce petabytes of candidate passwords.

These are made possible by a clever design described in the original paper, where a Predicate Function is applied on the hash value. When the server hashes a password from the cracking dataset, it doesn't need to check and compare this value to every password in the decoy set. That would be impossible. Instead, it uses the predicate function and check the bounds described by the vector describing the decoy set.

The Significance of 3PC

The implications of the 3PC protocol are profound for both privacy enhancement and security. For organizations, it offers a viable method to test the strength of password hashes without risking exposure of sensitive information to external parties. It aligns with privacy regulations and security best practices by providing a means to leverage powerful computational resources for hash cracking without compromising data privacy.

Moreover, the 3PC protocol addresses a critical need in the realm of cybersecurity—enabling secure, privacy-preserving computation in an increasingly interconnected digital environment. By allowing for the efficient use of third-party computational power, it opens new avenues for research, security testing, and the strengthening of password policies across various sectors.

In Conclusion

This post presents a method for privacy-preserving password cracking that leverages the computational power of an untrusted third party without disclosing the password hash. By utilizing anonymity sets to conceal the target hash, we overcome traditional limitations related to processing and storing a vast number of decoy hashes and their plaintext counterparts. This is achieved through an innovative application of predicate functions to hash function outputs. Furthermore, increasing number of decoy hashes does not affect the cracking speed, highlighting the 3PC protocol's efficiency. Practical application and efficiency of the protocol were validated through both toy examples and a real-life implementation on the RIVYERA FPGA cluster. The experiments confirmed the protocol's effectiveness in maintaining the target hash and plaintext password's confidentiality, safeguarding against the disclosure of the hash value or its pre-image, and ensure resistance against malicious tampering. Additionally, a proof of work mechanism provides clients with a basis to verify the completeness of the search effort. Theoretical analysis and empirical testing affirm the 3PC protocol's suitability for real-world applications, considering security, privacy, and performance. For the theoretical proofs and detailed steps, find the original publication below.

Based on:

N. Tihanyi, T. Bisztray, B. Borsos and S. Raveau, "Privacy-Preserving Password Cracking: How a Third Party Can Crack Our Password Hash Without Learning the Hash Value or the Cleartext," in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 19, pp. 2981-2996, 2024, doi: 10.1109/TIFS.2024.3356162. keywords: {Passwords;Protocols;Servers;Data privacy;Privacy;Hash functions;Probabilistic logic;Password security;hash cracking;k-anonymity;privacy enhancing technology;data privacy},